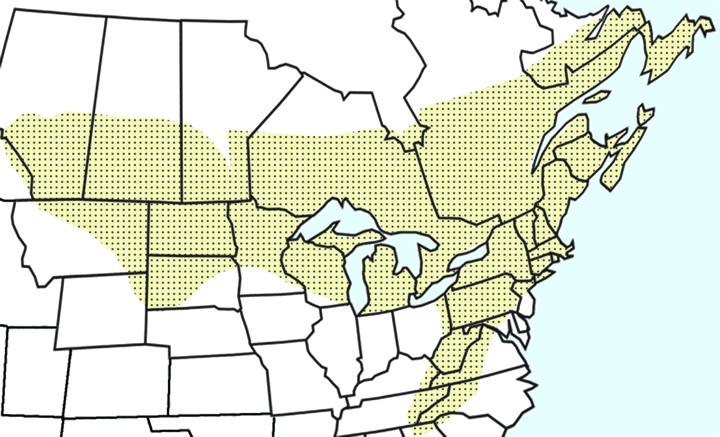

Historically this species held a large range from Newfoundland and the northeastern U.S., south along higher elevations of the Appalachians, west through North Dakota and the Canadian Great Plains, across much of Saskatchewan and Alberta, west into British Columbia.

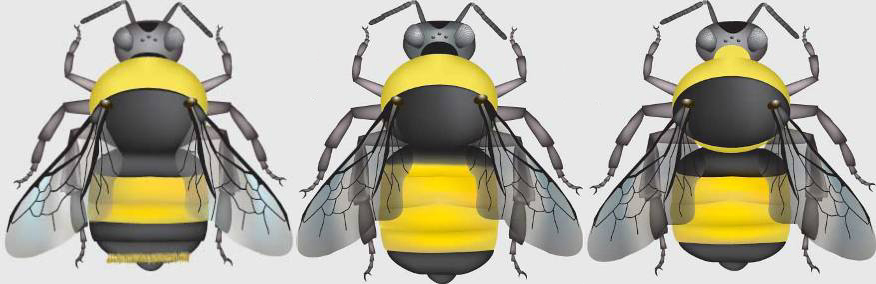

In order to properly identify bumble bees, you need to first determine whether the bee you are examining is male or female.

Yellowbanded bumble bee queens and workers have yellow on the front part of the thorax and the second and third abdominal segments. Otherwise their hair is primarily black including that on the legs and the base of the abdomen, with the exception of a fringe of brownish yellow hairs on the fifth abdominal segment. Their hair is nearly entirely black on the head. Coloration on the males is similar to the females except male B. terricola have pale yellowish hair on the front of the face and the top of the head. Similar bees that could occur in the same region are B. pensylvanicus and B. auricomus.

Yellowbanded bumble bee males have pale, yellowish on the front of their faces, with intermixed black hairs on the sides, and and mostly black hairs around the antennae. The top of the head has pale yellowish hairs intermixed with black, especially laterally. Their hair is pale yellowish on the front of the thorax and black over the posterior two-thirds of thorax. The second and third abdominal segments have bright yellow hair. Abdominal segments 1, 5 and 6 have mostly black hair with some pale hairs on segments 5 and 6.

Distinguishing B. terricola from B. pensylvanicus and B. auricomus

Females of B. pensylvanicus and B. auricomus have long faces in contrast to the round face of B. terricola. Females of B. pensylvanicus and B. auricomus have black only on the last two abdominal segments as opposed to B. terricola having the last three abdominal segments black with a fringe of brown hairs on segment 5. While male B. terricola have a prominent patch of yellow hair of the front of their faces, male B. auricomus and B. pensylvanicus have mostly black hair on the front of their faces. In addition, B. auricomus males have much larger eyes than B. terricola males.

For an online key, photographs of Yellow-banded bumble bee specimens and extensive identification information, visit the Discoverlife website.

Bumble bees are also excellent pollinators of many crops. Bumble bees are able to fly in cooler temperatures and lower light levels than many other bees, and they perform a behavior called “buzz pollination,” in which the bee grabs the pollen producing structure of the flower in her jaws and vibrates her wing musculature causing vibrations that dislodge pollen that would have otherwise remained trapped in the flower’s anthers. Some plants, including tomatoes, peppers, and cranberries, require buzz pollination.

All bumble bees belong to the genus Bombus within the family Apidae. The family Apidae includes the well-known honey bees and bumble bees, as well as carpenter bees, cuckoo bees, digger bees, stingless bees, and orchid bees. B. terricola belongs to a sub-genus of Bombus, Bombus sensu stricto. Bumble bees are important pollinators of wild flowering plants and crops. As generalist foragers, they do not depend on any one flower type. However, some plants do rely on bumble bees to achieve pollination. Loss of bumble bees can have far ranging ecological impacts due to their role as pollinators. In Britain and the Netherlands, where multiple bumble bee and other bee species have gone extinct, there is evidence of decline in the abundances of insect pollinated plants.

Until recently, the Yellow-banded Bumble Bee was commonly found east of the Rockies in the northern United States and into southern Canada, from eastern Montana and Alberta, across the northern states and southern portion of the Canadian provinces through to the east coast, with a southern extension along the Appalachian mountains in the eastern U.S. That U.S. states where the Yellow-banded bumble bee was formerly found include: Montana, South Dakota, North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, West Virginia, and portions of Ohio, Massachusetts, Maryland, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, and North Carolina. The Yellow-banded Bumble Bee has not been seen in most parts of its range in the U.S. since 1999, with the exception of records in a few locations in Wisconsin in 2007 and a single location in Pennsylvania in 2006. This bee has not been seen in many years in Tennessee, New York, Maine and Vermont, although it commonly occurred in these states in the past.

Numerous studies indicate that this species has declined, both regionally and locally, especially in the southern portion of its range. A recent long-term study in the Northeastern United States examining historical changes in bees found that, although this species did not exhibit the rapid and drastic population declines seen in B. ashtoni, B. pensylvanicus, and B. affinis, it did exhibit significant declines in relative abundance across its northeastern U.S. range. In another study comparing current and historical distributions of eight bumble bee species in the United States using museum records and nationwide survey data, it was found that relative abundances of B. terricola had sharply declined in recent years, from 10% relative abundance to less than 1%, in comparison with codistributed species. Read More

There are a number of threats facing bumble bees, any of which may be leading to the decline of the yellowbanded bumble bee. The major threats to bumble bees include: spread of pests and diseases by the commercial bumble bee industry, other pests and diseases, habitat destruction or alteration, pesticides, invasive species, natural pest or predator population cycles, and climate change.

Commercial bumble bee rearing may be the greatest threat to Bombus terricola. In North America, two bumble bee species have been commercially reared for pollination of greenhouse tomatoes and other crops: B. occidentalis and B. impatiens. Between 1992 and 1994, queens of B. occidentalis and B. impatiens were shipped to European rearing facilities, where colonies were produced then shipped back to the U.S. for commercial pollination. Bumble bee expert Robbin Thorp has hypothesized that these bumble bee colonies acquired a disease (probably a virulent strain of the microsporidian Nosema bombi) from a European bee that was in the same rearing facility, the Buff-tailed Bumble Bee (Bombus terrestris). The North American bumble bees would have had no prior resistance to this pathogen. Dr. Thorp hypothesizes that the disease then spread to wild populations of B. occidentalis and B. franklini in the West (from exposure to infected populations of commercially reared B. occidentalis), and B. affinis and B. terricola in the East (from exposure to commercially reared B. impatiens). In the late 1990’s, biologists began to notice that B. affinis, B. occidentalis, B. terricola, and B. franklini were severely declining.

Where these bees were once very common, they were nearly impossible to find. B. impatiens has not shown a dramatic decline; Robbin Thorp hypothesizes that B. impatiens may serve as a carrier of an exotic strain of Nosema bombi, although it may not be as severly affected by the disease as B. affinis, B. occidentalis, B. terricola, and B. franklini. B. affinis, B. occidentalis, B. terricola, and B. franklini are closely related to each other (they all belong to the subgenus Bombus sensu stricto). B. impatiens is not as closely related, which may explain the difference in sensitivity to a pathogen. This hypothesis is still in need of validation, although the timing, speed, and severity of the population crashes strongly supports the idea that an introduced disease caused the decline of bees.

The rearing company Koppert recently applied for a permit to transport the eastern species Bombus impatiens to California for crop pollination. The Xerces Society worked with bumble bee researchers to prepare comments to the USDA/APHIS discouraging the movement of these bees into new areas.

Besides the threat posed by the commercial bumble bee industry, there are many other threats to wild bumble bee populations. Bumble bees are threatened by many kinds of habitat alterations which may destroy, alter, fragment, degrade or reduce their food supply (flowers that produce the nectar and pollen they require), nest sites (e.g. abandoned rodent burrows and bird nests), and hibernation sites for over-wintering queens. Major threats that alter landscapes and habitat required by bumble bees include agricultural and urban development. Livestock grazing also may pose a threat to bumble bees, as animals remove flowering food sources, alter the vegetation community, and likely disturb nest sites. As bumble bee habitats become increasingly fragmented, the size of each population diminishes and inbreeding becomes more prevalent. Inbred populations of bumble bees show decreased genetic diversity and increased risk of decline.

Insecticide applications on farms poses a direct threat to foraging bumble bees. Insecticide application on Forest Service managed public lands for spruce budworm has been shown to cause massive kills of bumble bees and reduce pollination of nearby commercial blueberries in New Brunswick. Broad-spectrum herbicides used to control weeds can indirectly harm bumble bees by removing the flowers that would otherwise provide the bees with pollen and nectar.

Bumble bees are threatened by invasive plants and insects. The invasion and dominance of native grasslands by exotic plants may threaten bumble bees by directly competing with the native nectar and pollen plants that they rely upon. In the absence of fire, native conifers encroach upon many meadows, which removes habitat available to bumble bees. The small hive beetle (Aethina tumida) is an invasive parasite of the honeybee, yet it also infests bumble bee colonies. Its actual impact on bumble bee colonies could be severe, although it has not been well studied.

Global climate change also poses a real threat to bumble bees; anecdotal evidence has suggested that some of the bumble bee species adapted to cool temperatures are in decline, whereas warmer adapted species are expanding their ranges. Baseline data and long term monitoring are needed to better understand the true impact of climate change on bumble bees.

Much of the content for this page was developed from a status review, co-authored by professor emeritus Robbin Thorp (U.C. Davis Department of Entomology), Elaine Evans, and Scott Hoffman Black (Xerces). Bee illustrations were provided by Elaine Evans.

Funding for our efforts to conserve bumble bees in decline has been generously provided by the CS Fund and Xerces Society members.