Enacted on October 18, 1972, the Clean Water Act revolutionized the way in which waterways and pollution are managed, but there is still further to go.

Revolutionizing the way in which waterways and pollution are managed, and reinforcing a burgeoning national consciousness of the importance of quite literally cleaning up our act, the Clean Water Act is a key milestone in United States environmental history. Enacted on October 18, 1972, the Clean Water Act—otherwise known as the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972—ushered in an era of stricter pollution standards amid public and scientific concern about the state of U.S. waterways.

Famously, in 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Ohio caught on fire, an event that was disseminated to an outraged public by significant news outlets, including Time, which described the Cuyahoga as a river that “oozes rather than flows,” and in which a person “does not drown but decays.” This emphatic article (available online here) also decried the significant pollution of other rivers across the country, including how “the Potomac reaches the nation’s capital as a pleasant stream, and leaves it stinking from the 240 million gallons of wastes that are flushed into it daily.” These striking phrases, and equally impactful photos, helped to galvanize public outrage over the state of U.S. waterways—and the Cuyahoga remains a significant symbol to this day.

Although obviously a river being so polluted that it catches on fire should be considered newsworthy, the timing of all this is somewhat puzzling at first glance. After all, the Cuyahoga River had been periodically catching on fire since the late 1800s. In fact, the 1969 Cuyahoga fire was neither the most destructive, nor the most deadly, of these blazes. The most deadly fire on the Cuyahoga occurred in 1912, claiming five lives. The most costly fire, meanwhile, occurred in 1952, when a conflagration on the Cuyahoga decimated boats, a bridge, and a riverfront office building, causing $1 million in damages. Adjusted for inflation, that would be over $9 million today. (All the Cuyahoga blazes are detailed here.) These stories were covered by local news outlets, but did not achieve the same sort of national outcry that the 1969 fire did.

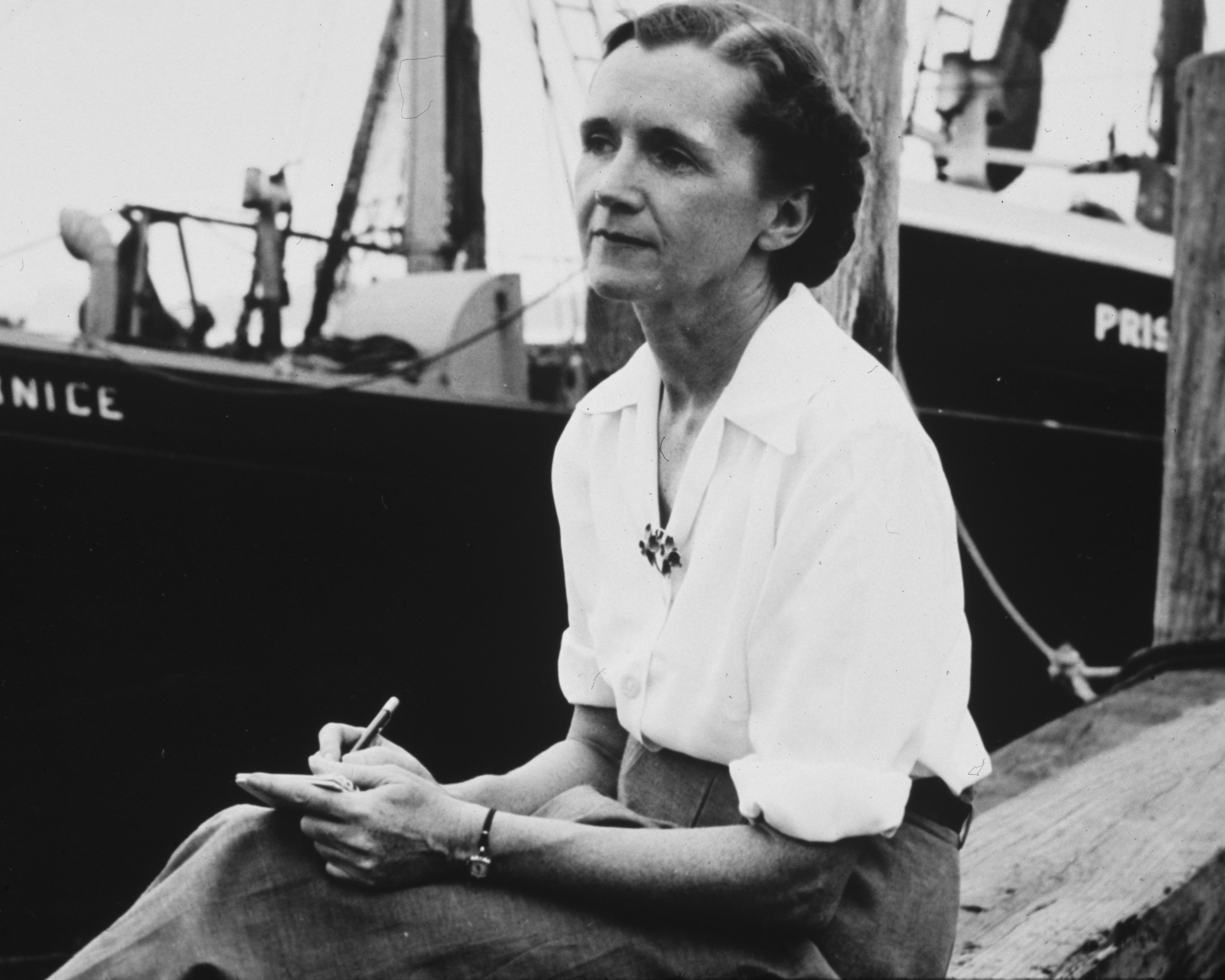

The key difference is that, by the time of the 1969 Cuyahoga fire, the burgeoning environmental movement had laid the groundwork for the press, the public, and ultimately, politicians, to take notice and to take action. Seven years before, Rachel Carson’s masterpiece Silent Spring was published, galvanizing public opinion on pesticides and introducing a more comprehensive environmental ethos. Prior to that, Carson’s bestselling books about marine ecology, and Jacques Cousteau’s book The Silent World brought the underwater realm to the public consciousness.

Various other written works emerged, decrying environmental degradation and promoting new ways of viewing humanity’s place in the world. Teach-ins and protests occurred. Fledgling environmental legislation such as California’s first automobile emissions standards (originally implemented in 1961) and national laws, including various iterations of the 1948 Federal Water Pollution Control Act and the 1965 Water Quality Act, pushed Americans to reduce their collective impact on the environment. The stage was also set, of course, by the establishment of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970.

The 1972 passage of the Clean Water Act, which strove to “eliminate” the “discharge of pollutants” and make all U.S. waterways “fishable and swimmable” by 1985, reflected how far we had come as a nation in recognizing the significance of healthy waterways, and reflected a growing commitment to protecting them. In more concrete terms, the Clean Water Act established a comprehensive means of protecting our nation’s waterways. In particular, the fact that the EPA was to implement Clean Water Act regulations and enforcement was a significant step forward. The 1948 Federal Water Pollution Control Act left that very vague authority to the states, resulting in piecemeal enforcement—and often inaction. In contrast, the Clean Water Act brought forth actual provisions for federal—and thus comprehensive—enforcement, and stronger standards.

Since the passage of the Clean Water Act, there have been some significant gains in the improvement of water quality and the health of aquatic ecosystems. According to the National Wildlife Federation, on the Clean Water Act’s 45-year anniversary in 2017, “Over the past four decades, the rate of wetland loss slowed, rivers stopped catching fire, and the number of waters that meet clean water goals nationwide has doubled.”

Even the Cuyahoga River, with its long history of flammability, is recovering. Thanks to extensive efforts by federal and state agencies, nonprofits, and community members, “The river lives. Fish populations, health, and variety of species have increased hundreds-fold, recreational activity has grown, and new riverside residential and commercial development speaks to the belief that the river is a good place to live, a resource to protect, and a destination to invest in,” according to Cuyahoga River Restoration, a nonprofit working to restore and protect the environmental quality of the Cuyahoga River.

However, there is still a lot of room for improvement. The U.S. missed its 1985 deadline for all waterways becoming “fishable and swimmable,” and we are, in fact, still waiting on that 33 years later. Water bodies of all kinds still face pollution issues. A very telling example is the fact that the Gulf of Mexico’s “dead zone”—a biological desert where oxygen levels are too low to support marine life—reached its largest recorded size in 2017. Although some dead zones occur naturally, many are caused by humans. In the case of the Gulf of Mexico, agricultural runoff is to blame, which is carried to sea by the Mississippi River.

Also, according to the 2012 National Lakes Assessment published by the EPA, 35 percent of lakes surveyed had excess nitrogen, 40 percent had excess phosphorus, and 31 percent “have degraded benthic macroinvertebrate communities, which include small aquatic creatures like snails and mayflies.” In other words, agricultural runoff has also impacted a significant number of lakes, depleting many vital species. Freshwater mussels are another key example of the impacts of water pollution on invertebrates. Although these filter feeders can significantly improve water quality, they have their limits. High levels of pollutants can kill freshwater mussels, a component of their decline across much of the country (as explained here). Indeed, water pollution does not just affect humans; it can also impact the well-being of invertebrates—and entire ecosystems.

All of this arguably indicates that we should be strengthening Clean Water Act regulations—and we did in 2015, with the Clean Water Rule, which clarified the definition of “waterways of the United States” to include streams and wetlands. These vital aquatic ecosystems support a wide array of species, and indirectly influence the water quality of rivers and lakes. Other key revisions to the Clean Water Act from 2015 included limiting the pollution that electric power plants can discharge into waterways and regulating the disposal of coal ash to prevent ground and surface water contamination.

Sadly, the current administration has repealed those 2015 revisions, and is weakening the EPA itself—the very agency responsible for overseeing and implementing Clean Water Act standards. A particularly concerning trend involves the fact that current recipients of EPA grants are now barred from serving on the Science Advisory Board (SAB) and other panels. The result is that industry officials have taken the place of scientists in various advisory positions, which sets a discouraging precedent.

Although the future of our nation’s water is currently murky, we still have time to make things right. We have the past successes of the environmental movement for inspiration, and the research and recommendations of hundreds of modern scientists to strive towards. Remember: We have once before risen from the literal ashes of a burning river to evince positive, albeit incomplete, change for our nation’s waterways. We are capable of rising together to make a difference for our water, and for the creatures that depend upon it—from invertebrates to humans.

Learn more about the Xerces Society’s work to protect freshwater mussels and aquatic ecosystems.

Further Reading

Read more about legislation and policy on the blog.

Find more stories of conservation history and heroes.