Once, millions of monarchs overwintered annually along the Pacific coast in California and Baja, Mexico. But by the mid-2010s, the population had declined to hundreds of thousands of butterflies, a >90% decline from the 1980s. In the winters between 2018-2020, the annual Xerces Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count tallied under 30,000 monarchs—record low counts. In 2021 and 2022, the population made a modest bounce back to mid-2010s numbers with a count of >200,000. However, the population still remains perilously small and vulnerable to yearly fluctuations.

While the yearly up-and-downs of the population garners a lot of attention, the real issue is the longer-term population decline due to stressors such as habitat loss and degradation, pesticides, and climate change—as well as other pressures on the migratory cycle of the monarch that we still have yet to fully study or comprehend. There are no quick fixes to solve all these large and complex forces, but we can all take actions–both big and small–to help save monarchs as well as the many other butterfly and bee species that need our help.

This Western Monarch Call to Action, led by the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, aims to provide a set of rapid-response conservation actions that, if applied immediately, can help the western monarch population bounce back from its critically low overwintering size. We recognize and support longer-term recovery efforts in place for western monarchs such as the Western Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA) plan and Monarch Joint Venture (MJV) implementation plan. The goal of this call to action, however, is to identify actions that can be implemented in the short-term, to avoid a total collapse of the western monarch migration and set the stage for longer-term efforts to have time to start making a difference.

The five key steps to recovering the western monarch population in the short term are:

- Protect and manage California overwintering sites

- Restore breeding and migratory habitat in California

- Protect monarchs and their habitat from pesticides

- Protect, manage, and restore summer breeding and fall migration monarch habitat outside of California

- Answer key research questions about how to best aid western monarch recovery

Read our overarching recommendations below—which apply to everyone from land managers to individuals—or click here to download the Call to Action as a PDF. You can also jump to actions that individuals can take to support western monarchs.

The science investigating monarch declines is active and ongoing, but the severity of the recent declines means that we need to act based on the available evidence. The western monarch population may collapse completely if we wait until all of the answers are fully in focus. Thus, the actions listed below are based on our current understanding of stressors that impact the monarch, as well as butterflies more generally, and on a precautionary principle that suggests we should always act to reduce harm.

We need to halt the destruction of overwintering habitat. We need to work at local, regional, and state levels to ensure that overwintering sites in California have sufficient legal and enforced protection.

- Each year, overwintering sites—even some which are legally protected—are destroyed or damaged by human actions like development or inappropriate tree trimming, sometimes leading to total abandonment of a site by the butterflies.

We need to create and implement overwintering site management plans at as many overwintering sites as possible that have hosted significant numbers of monarchs in recent years.

- See Protecting California’s Butterfly Groves: Management Guidelines for Monarch Butterfly Overwintering Habitat, published by the Xerces Society, for guidance on managing overwintering sites.

- You can adopt an overwintering site and become an advocate for the site’s protection and active management. Contact your local elected official to ask that monarch overwintering sites in your area be protected.

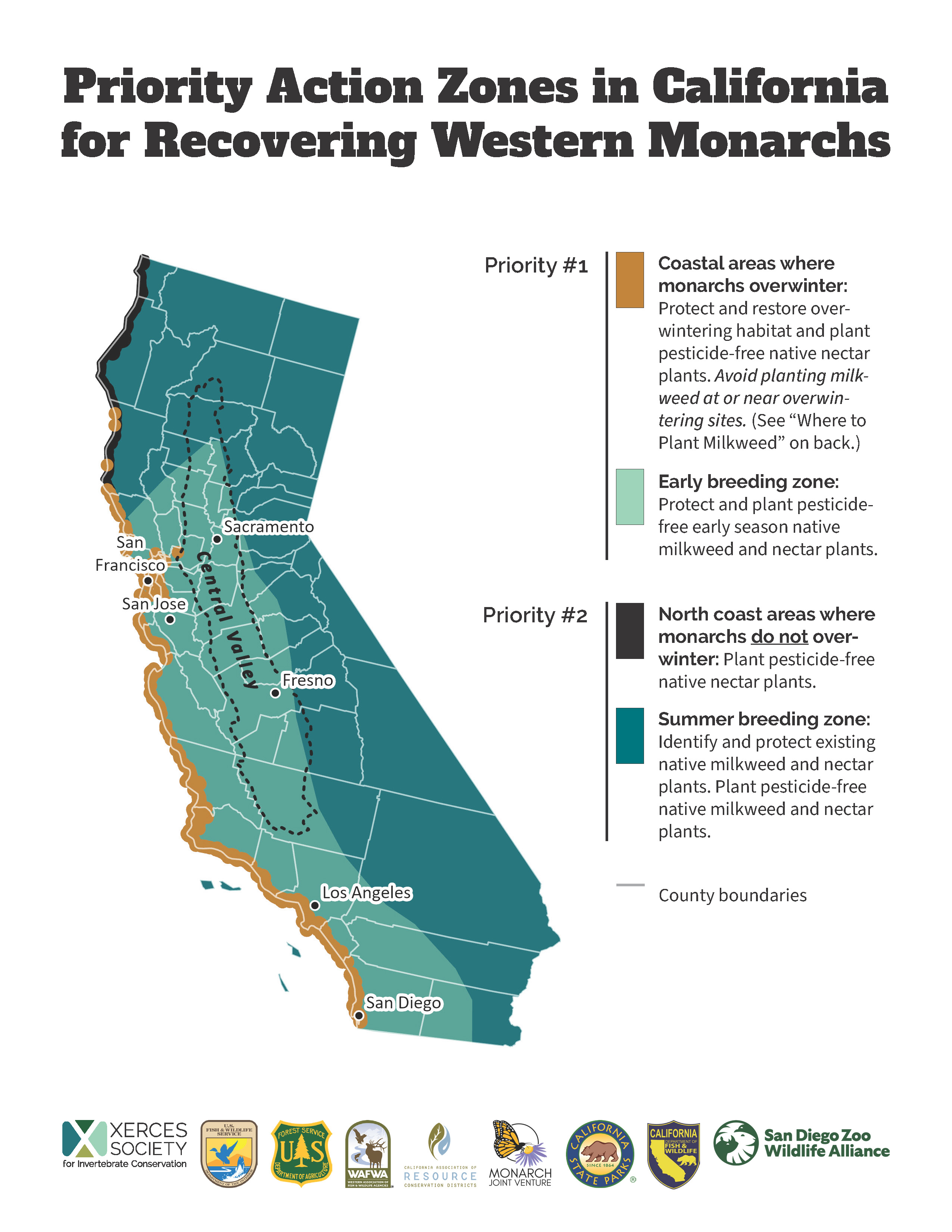

The primary focus for habitat restoration should be the Coast Range, Central Valley, and the foothills of the Sierra Nevada—areas critical to producing the first generation of monarchs in the spring.

We need Californians to plant nectar species, especially flowers that bloom in the early spring (February–April) to provide critical nectaring resources for monarchs.

- Plant flowers which are attractive to monarchs and other butterflies. Ideally, these would be native species which are adapted for climate change and which benefit other insects as well, but monarchs are fairly generalized in their nectar habits and can benefit from a wide range of flowering plants.

- Particular emphasis should be placed on planting species which bloom early in the spring (blooming February–April), but also the fall (September–October). If you live near the coast, winter blooming (November–January) species are also valuable for overwintering monarchs to nectar on.

- Click here to find a nectar plant list for your region.

We need Californians to plant native milkweed, especially species which emerge earliest and are already at the seedling or transplant stage.

- Early emerging species native to California include woollypod (Asclepias eriocarpa), California (A. californica), and heartleaf (A. cordifolia) milkweeds; later-emerging native species with more seed availability include narrowleaf (A. fascicularis) and showy (A. speciosa) milkweeds.

- In the desert southwest of California, plant rush (A. subulata) and desert (A. erosa) milkweeds. In all cases, plant milkweed species native to California, and ideally, to your area.

- Also, ideally, plant milkweed greater than 5 miles inland from the coast, if you live north of Santa Barbara. Milkweed doesn’t naturally grow close to the coast north of Santa Barbara and milkweed at overwintering sites can interrupt natural monarch overwintering behavior.

- Click to access the Milkweed Seed Finder to get regional lists of plant nurseries and seed companies.

We need to work towards increasing native milkweed and nectar plant availability for both seeds and transplants.

- Ask your local nursery to start supplying native milkweed. Organize a group to collect milkweed seed and propagate it.

- Engage with seed companies, plant nurseries, and land management entities to work together to ramp up production and ensure a diverse supply of native milkweeds and nectar plants which are insecticide free.

We need to plant more native milkweed from seed and remove tropical milkweed to replace it with native milkweed and nectar plants.

- Tropical milkweed—a nonnative species which stays evergreen and does not die back in areas with mild winters—interrupts the monarchs’ natural migratory cycle, leading to disease build-up and winter breeding which are both associated with poorer outcomes for monarchs, further exacerbating other stressors on the population. If you already have tropical milkweed in your garden, it is very important to cut it back to the ground in the fall (October/November) and repeatedly throughout the winter to mimic native milkweed phenology and break the disease cycle. Ideally, tropical milkweed should be removed entirely and replaced with native milkweed and/or nectar species. Click here to learn more about problems associated with tropical milkweed.

We need to halt all cosmetic use of pesticides. Seek out non-chemical options to prevent and manage pests in your garden and landscaping.

We need to push to suspend the use of neonicotinoids in the commercial production of milkweed plants.

We need to work to reduce herbicide and insecticide use in and around overwintering sites and in key breeding regions.

- Avoid herbicide applications that might damage monarch breeding and migratory habitat such as milkweed and flowering plants. Use targeted application methods, avoid large-scale broadcast applications of herbicides, and take precautions to limit off-site movement of herbicides.

- Neonicotinoid insecticides, in particular, should be avoided at all times in monarch habitat due to their persistence, systemic nature, and toxicity.

- Click to check out pesticide reduction resources.

Garden plants are frequently treated with insecticides to prevent unsightly holes rather than to promote healthy plants. Such cosmetic use should be banned as the chemicals can harm flower-visiting insects. (Photo: Xerces Society / Matthew Shepherd)

Identify existing monarch habitat so you can work to protect it from destruction.

- Plan field surveys, use the habitat suitability model to identify key areas, and learn milkweed species which may occur in your area. More information available here.

- Make a plan on how to protect that habitat this year.

Manage monarch habitat in a way that minimizes harm.

- Conduct management activities such as mowing, burning, and grazing in monarch breeding and migratory habitat outside of the period when monarchs are present.

- See the Xerces Society fact sheet Timing Management in Monarch Breeding Habitat to learn when it’s best to manage habitat without harming monarchs.

Restore monarch habitat, particularly in areas highly suitable for monarchs and where habitat has been lost.

- Habitat restoration in regions where monarch habitat historically occurred, but has been lost (such as the Columbia Plateau, Snake River Plain, and riparian areas) is of the highest priority outside of California. See our Habitat Suitability Models to preview maps of the areas with the highest monarch habitat suitability in the West. Contact [email protected] if you are interested in receiving copies of the associated map products for planning or research purposes.

- We do not generally recommend planting milkweed outside of its native range (e.g., coastal Washington or in high elevation forests); while planting milkweed in these areas may not be harmful, it is unlikely to be effective for monarch conservation in the near-term.

- While milkweed may not be a limiting factor for monarchs in all parts of their western range, restoring natural habitat or planting a pollinator garden that includes milkweed may be beneficial to monarchs and other pollinators.

- As with all habitat restoration, consider how restoration actions can be made to be as climate-resilient as possible. Click to view our publication series Climate-Smart Habitat for Pollinators.

We need Californians and Arizonans to collect observations of monarchs and milkweeds, especially in the early spring (February–April), the period in which monarchs leave the overwintering sites.

- This is the period of the year we know the least about monarch location and behavior, as well as milkweed availability.

We need research at overwintering sites and suspected early spring breeding sites to understand when monarchs are leaving the overwintering sites, if they are leaving earlier than in the past.

- This requires additional late winter/early spring monitoring at overwintering sites and targeted research to analyze existing datasets.

We need eyes looking out for monarchs across the rest of the West, too, in particular, in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Montana.

- Together these observations will help answer questions about monarch breeding phenology and whether the West sees an influx of monarchs returning from Mexico. Answering these questions will directly help inform conservation strategies. Report all monarch adult, caterpillar, egg, nectaring, and milkweed sightings to the Western Monarch Milkweed Mapper.

We need more research to answer other key questions to help target and refine conservation efforts. For example: Where are monarchs facing high levels of pesticide contamination and how can we minimize negative impacts of pesticides on monarchs? What are the causes of high overwintering mortality and how can we lower mortality risk at overwintering sites?

The effectiveness of western monarch conservation efforts depends upon getting a lot of people involved, quickly. Spread the word, including on social media. Use the hashtag #SaveWesternMonarchs on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to raise awareness, and add a Save Western Monarchs frame to your Facebook profile picture!

Similarly, share your story! Tell us about your work to save western monarchs and you just might get featured on our blog, which will help to inform and inspire others! Email your work to [email protected] and [email protected].

The Xerces Society’s work is only possible with the support of donors like you. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation today.

Do you need help putting this call to action into action? Providing technical assistance to create, restore, manage, and protect monarch and pollinator habitat to agencies, tribes, nonprofits, and others is a core part of Xerces' work. Check out the links above for more information and resources first. If you have further questions or want to connect your work as part of this call to action, contact us at [email protected].

Thank you to the western monarch researchers and partners with whom conversations about the most effective actions we need to take helped form the basis of this call to action, including Wendy Caldwell, coordinator of the Monarch Joint Venture; Abi Convery, planning biologist for Ventura County; Elizabeth Crone, professor at Tufts University; Matt Forister, professor at University of Nevada–Reno; Jessica Griffiths, Charis van der Heide, and Dan Meade, overwintering site biologists in California; David James, associate professor at Washington State University; Karen Miner, biologist with California Department of Fish and Wildlife; Mia Monroe, cofounder of the Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count; Gail Morris, coordinator of the nonprofit Southwest Monarch Study; Ann Potter, biologist for Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife; Robert M. Pyle, founder of the Xerces Society; Cheryl Schultz, associate professor at Washington State University; Francis Villablanca, professor at Cal Poly; Beth Waterbury, retired biologist for Idaho Department of Fish and Game; Louie Yang, associate professor at University of California–Davis; and others.

Thank you to all the Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count volunteers and regional coordinators whose dedication makes understanding the population’s status possible.

Thank you, too, to all the individuals and groups already doing good work on behalf of monarch conservation. Your work is critical—keep it up!

Espeset, A. E., J. G. Harrison, A. M. Shapiro, C. C. Nice, J. H. Thorne, D. P. Waetjen, J. A. Fordyce, and M. L.Forister. 2016. Understanding a migratory species in a changing world: climatic effects and demographic declines in the western monarch revealed by four decades of intensive monitoring. Oecologia 181:819–830.

Pyle, R. M., and M. Monroe. 2004. Conservation of Western Monarchs. Wings 27(1):13–17.

Schultz, C. B., L. M. Brown, E. Pelton, and E. E. Crone. 2017. Citizen science monitoring demonstrates dramatic declines of monarch butterflies in western North America. Biological Conservation 214:343–346.

%20banner%20crop.jpg)

-in-rangeland%2C-Nevada_XS-SMcK-crop.jpg)