At Xerces, our love for pollinators is a year-round affair. In honor of Pollinator Week 2022, we’ve asked our staff to share some of their very favorite flower-buzzers and why they love them. We hope you find a new friend or a familiar face on this list, and we’d love to hear which pollinator you carry a torch for, too. Head to our social media accounts on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter and drop us a note!

Andrena Carolina, long-faced Carolina mining bee

Nominated by Emily May

Emily studied wild bees in Michigan's highbush blueberry fields, where she developed a special love for the long-faced Carolina mining bee (Andrena carolina), one of several species of wild bees that specialize on blueberries (Vaccinium sp.) in eastern North America.

“This bee's long face helps it reach into the deep flowers of blueberries, and its flight season is tightly linked with its spring-blooming host plants. Next time you eat a blueberry, remember to thank Andrena carolina and other pollinators for your sweet treat!”

Andrena erigeniae, spring beauty mining bee

Nominated by Kelly Gill

Some bees are picky eaters, requiring pollen from certain plant families, genera, or species to complete their life cycle. A. erigeniae is one such example, a solitary ground-nesting bee that can be found in temperate forest habitats from MN to NY and south to NC and GA.

“These small mining bees emerge from their underground nests in sync with the early-spring bloom of spring beauty (Claytonia virginica, C. caroliniana) and can be observed foraging in the forest understory carrying copious amounts of the flower's pink pollen back to their nest to provision brood cells with food for developing larvae. We see them during that magical, fleeting time of year when the forest understory catches a glimpse of sunlight before trees leaf-out and shade the understory.”

Augochlora pura, pure golden green sweat bee

Nominated by Kass Urban-Mead

These shiny green sweat bees nest in rotting logs and are widespread across Eastern and Midwestern North America.

“A familiar flower visitor in gardens, I've found them nesting both in wooden benches in city parks as well as in dead snags and stumps miles into the forest. I am always amazed by these glistening jewels of bees, with their shining iridescent exoskeletons. Many other forest-loving beetles and insects are iridescent, too: ecologists guess that light glinting off them as they flit between dappled sun and shade may confuse predators. One time I climbed to the tippy top of a big old red oak tree – safely, with ropes and harness – and there, in a dead branch 65 feet in the sky, was a vibrant nest of shiny green sweat bees! I've had a soft spot for these bees ever since.”

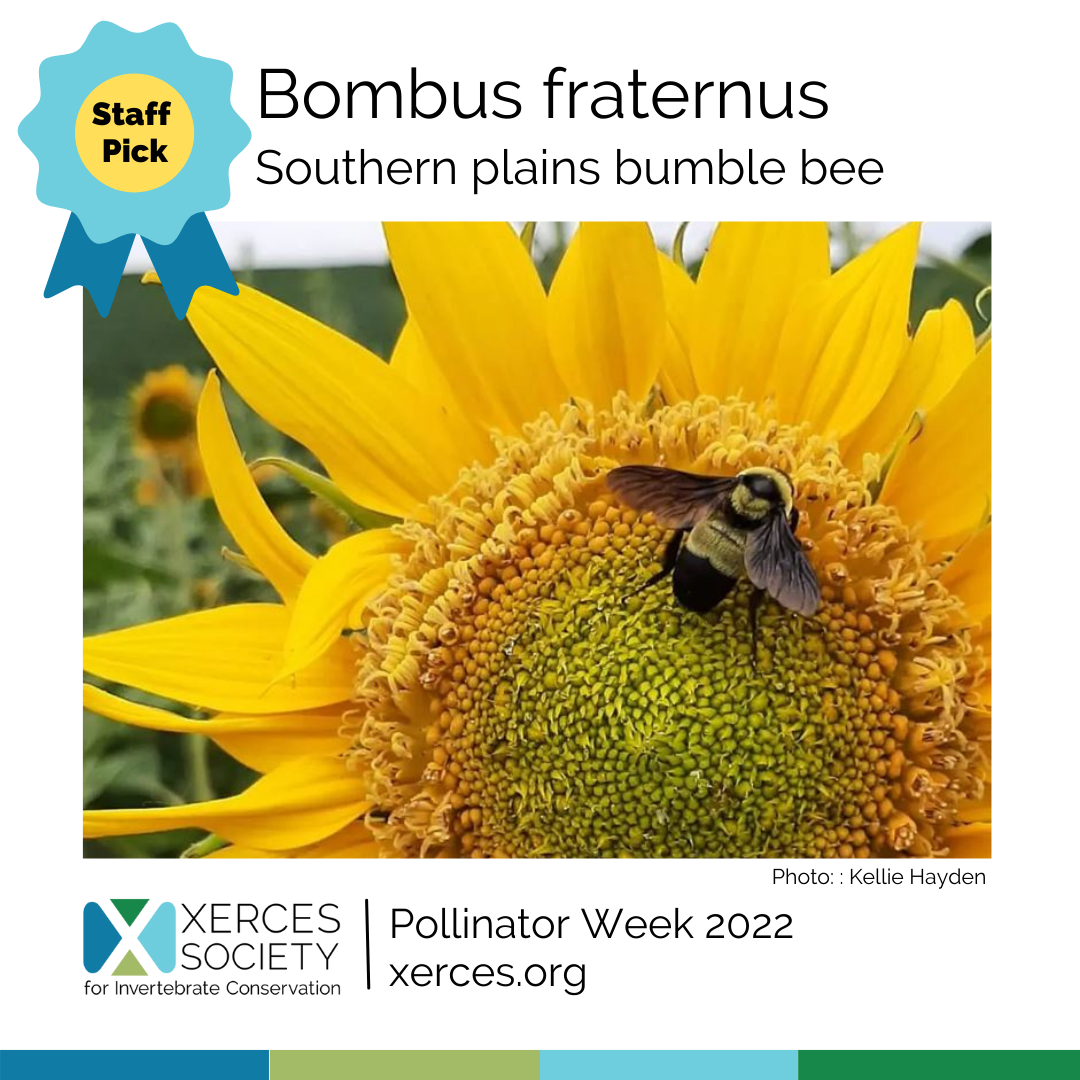

Bombus fraternus, southern plains bumble bee

Nominated by Kellie Hayden

Bombus fraternus is found in the Eastern Temperate Forest region on the coastal plain of the southeastern United States from central Florida north to New Jersey, Ohio west throughout the United States Great Plains.

“This is the species that got me interested in entomology, and got me over my fear/avoidance of insects. Before encountering B. fraternus, I had never even considered that there were different bumble bee species out there.

“This purple coneflower image is the exact B. fraternus that got me started. That one is a queen, and easily the biggest bumble bee I have ever seen in my life. I was both anxious and in awe of her.”

Bombus ternarius, tri-colored bumble bee

Nominated by Sarah Foltz-Jordan

Sarah chose this bee because it is one the most handsome (and common) bumble bees in the north woods of Minnesota, where she lives, as well as one of the soonest to emerge in spring. The tri-colored bee is associated with forested and wetland habitats.

“I saw an aggregation of over 20 tri-colored queens in my yard this year, hunkered down together after a sudden rain-storm changed their foraging plans. People often mistake this bee for the federally endangered rusty-patched bumble bee, but the patch on the rusty-patched is much smaller and more dull-colored, compared to the tri-colored bee. Both bees are a lovely sight to behold, and essential for ecosystem health.”

Hemaris diffinis, snowberry clearwing moth

Nominated by Jennifer Hopwood

These moths are found east of the continental divide in a variety of habitats, including gardens, parks, farms, roadsides, and more. Snowberry clearwing moth caterpillars are found on snowberry, viburnum, hawthorn, and honeysuckle plants, and adults fly from March to September, with two generations a growing season.

“What's not to like about hummingbird moths? It's so much fun to watch them as they hover over flowers, extending their long tongues inside to sip nectar.”

Megachile spp, leaf-cutter bees

Nominated by Mace Vaughan and Corin Pease

Corin and Mace both keep sharing with audiences at pollinator conservation trainings how leaf-cutter bees, found all over the world, are their favorite pollinators. Both Corin and Mace like how they store pollen in a huge pillow on the bottom of their abdomens, not to mention the cool circles and ovals they leave behind when gathering leaf pieces.

Mace says, “Their brusque behavior and pugnacious attitude at the flowers and how they will stick their abdomens and stinger in the air if harassed is charming.”

Corin says, “I’m always impressed by how their heads and jaws are so big and burly, showing off where they keep the huge muscles that let them carve off pieces of leaf and petal for their nest.”

Toxomerus geminatus, Eastern calligrapher syrphid flies

Nominated by Alina Harris

Native and observed in Northeastern North America, the adults of Eastern Calligrapher syrphid flies (Toxomerus geminatus) can be found sipping nectar from shallow flowers in diverse habitats, while their eggs and larvae can be found on crops nearby colonies of aphids.

“Aphid-eating syrphid flies are my garden allies! Last year I observed plump Toxomerus geminatus adults foraging from the native flower called Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) and later, their offspring eating the aphids that were attacking my cabbage plants. They're also known to eat mites. I love the ecosystem services that syrphid flies provide in natural and agricultural systems, all the while being so ornate and pretty!”