Bees are the most important group of pollinators. With the exception of a few species of wasps, only bees deliberately gather pollen to bring back to their nests for their offspring. Bees also exhibit a behavior called flower constancy, meaning that they repeatedly visit one particular plant species on any given foraging trip.

On a single foraging trip, a female bee may visit hundreds of flowers, transferring pollen the entire way. In contrast, butterflies, moths, flies, wasps, and beetles visit flowers to feed on nectar (or on the flower itself, in the case of some beetles) and not to collect pollen. Thus, they come in contact less frequently with the flower’s anthers than bees do.

Bees are immensely diverse insects that form an important group within the Hymenoptera, an insect order that also includes ants, wasps, and sawflies. Worldwide, there are an estimated 20,000 species of bees, with approximately 3,600 species native to North America north of Mexico. North American species range in length from about 1/12 inch to more than 1 inch (2–25 mm). They vary in color from dark brown or black to red or metallic green and blue; some have stripes of white, orange, yellow, or black; and some even have opalescent bands.

Solitary Bee Lifecycle

Of the roughly 3,600 species of bees in North America, more than 90 percent lead solitary rather than social lives, each female constructing and provisioning her own nest without any help from other members of her species. Solitary bees usually live for about a year, although humans only see the active adult stage, which lasts about three to six weeks. These insects spend the other months hidden in a nest, growing through the egg, larval, and pupal stages.

Female solitary bees have amazing engineering skills, going to extraordinary lengths to construct a secure nest. About 30 percent of solitary bee species use abandoned beetle burrows or other tunnels in snags (dead or dying standing trees). Alternatively, they may chew out a nest within the soft central pith of stems and twigs. The other roughly 70 percent nest in the ground, digging tunnels in bare or sparsely vegetated, well-drained soil. A few species nest in eclectic places such as empty snail shells and potlike cells that they construct on twigs from pebbles and tree resin.

Each bee nest usually has several separate brood cells in which the female lays her eggs, one egg per cell. The number of cells varies by species. While some nests may have only a single cell, most have five or even many more. Female woodnesting bees make cells in a single line that fills the tunnel. Females of ground-nesting species may dig complex, branching tunnels. To protect the developing bee and its food supply (from drying out, excess moisture, fungi, and disease) the cell may be lined with waxy or cellophane-like glandular secretions, pieces of leaf or petal, mud, or chewed-up wood.

The many solitary bee species exhibit a range of nesting behaviors. Some share a nesting site, sometimes in large aggregations or at great densities. For example, in well-established nesting sites of alkali bees (Nomia melanderi), 200 or more females may nest in a single square yard of ground, each bee tending a separate burrow. A few “solitary” species are communal in that they share a common entrance tunnel to the nest, but each female creates her own brood cells. More unusual are the large carpenter bees (genus Xylocopa): these females live long enough to meet — and share the nest with — their adult offspring.

Species At Risk

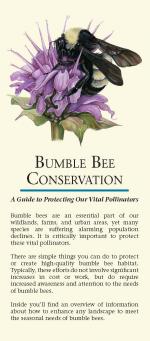

Many of our native bee pollinators are at risk, and the status of many more is unknown. Habitat loss, alteration, and fragmentation, pesticide use, climate change and introduced diseases all contribute to declines of bees. The Xerces Society advocates on behalf of bees. Our work has led to federal and state protections for a number of species leading to over half a million acres protected for these important animals. We are working with scientists and citizen monitors to understand the status of declining bumble bees and other rare species. We also work with lawmakers on legislation that encourages pollinator-friendly habitat restoration and consult with farmers, homeowners, and land stewards to restore the landscape for the benefit of bee pollinators.

We do not know the status of most bees because there are so many species. Unfortunately, all indication, suggest bees are in decline based on assessments of specific groups of bees. A recent analysis by the Xerces Society and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) found that 28% of bumble bees in Canada, the United States, and Mexico are in an IUCN Threatened Category. According to NatureServe, 50% of leafcutter bee species and 27% of mason bee species are “at risk”.

See our Species Profile page for more information on key species Xerces is working to protect.

Food in the form of abundant flowering plants that provide access to pollen and nectar throughout the growing season

Access to shelter and nesting sites including host plants for butterflies, pithy-stems and dead wood for cavity-nesting bees, and bare earth for ground-nesting bees

Protection from pesticides which kill non-target insects and degrade habitat by removing or contaminating flowering plants

Advocates who are willing to make changes in their own landscape, but also teach others and spread the word to encourage pollinator- friendly practices in their community.

Create, Restore, and Manage Habitat

From expansive meadows to backyard butterfly gardens and everywhere in between - every landscape can be optimized to support pollinators.

Provide Access to Nesting Sites

Like us, pollinators need a place to call home. Nesting resources can take many forms - from natural to man-made.

Managing Pests While Protecting Pollinators

Whether conventional or organic, all pesticides can pose a risk to pollinators if not used properly. Learn about the risks pesticides pose to pollinators, what measures can be used to reduce harm, and the many alternatives available to foster alternative methods of pest control.

Pick the Right Plants

We’ve prepared research-based, regionally appropriate plant lists and guides to help you pick the very best plants for pollinators.